Stargazers received a spectacular treat in parts of the U.S. and Europe on Thursday when the northern lights appeared in skies much farther south than they’re typically ever seen.

The pink, purple, blue and green light show was documented in parts of England, Germany, and as far south as Florida in the U.S.

The aurora borealis, as the lights are also known, is typically seen in the upper parts of the Northern Hemisphere around the Arctic Circle (places like Canada, Alaska, Greenland, Norway, Finland and Sweden). But scientists say a powerful solar storm caused the dazzling lights to appear at unusually low latitudes this week.

Here’s what happened, and when and why the lights may be visible again.

What causes them?

The northern lights are the result of a geomagnetic storm in the Earth’s magnetic field, originating from a massive explosion on the sun, called a solar flare, according to the South African National Space Agency, which has been monitoring a number of large solar flares in recent weeks. (One flare documented on Oct. 3 was described as the strongest Earth-facing solar flare recorded by SANSA in the past seven years.)

Particles from these massive bursts of energy travel into the Earth’s atmosphere and form colored lights upon contact with the atmospheric gases — with blue and purple appearing from nitrogen, and green and red appearing from oxygen, as the Center for Science and Education at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research explains.

And while dazzling, these geomagnetic storms can have potentially harmful effects on power grids and communication and navigation systems.

Low-Earth orbit satellites and high-frequency communication signals can experience disruptions; power grids — already weakened by recent storms — can face additional stress; and navigation systems like GPS can have a degraded quality, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said this week.

Due to ongoing recovery efforts related to Hurricanes Helene and Milton, NOAA said it released multiple warnings, including to the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the North American power grid, so people could better prepare ahead of this solar storm.

Where and when are the lights expected next?

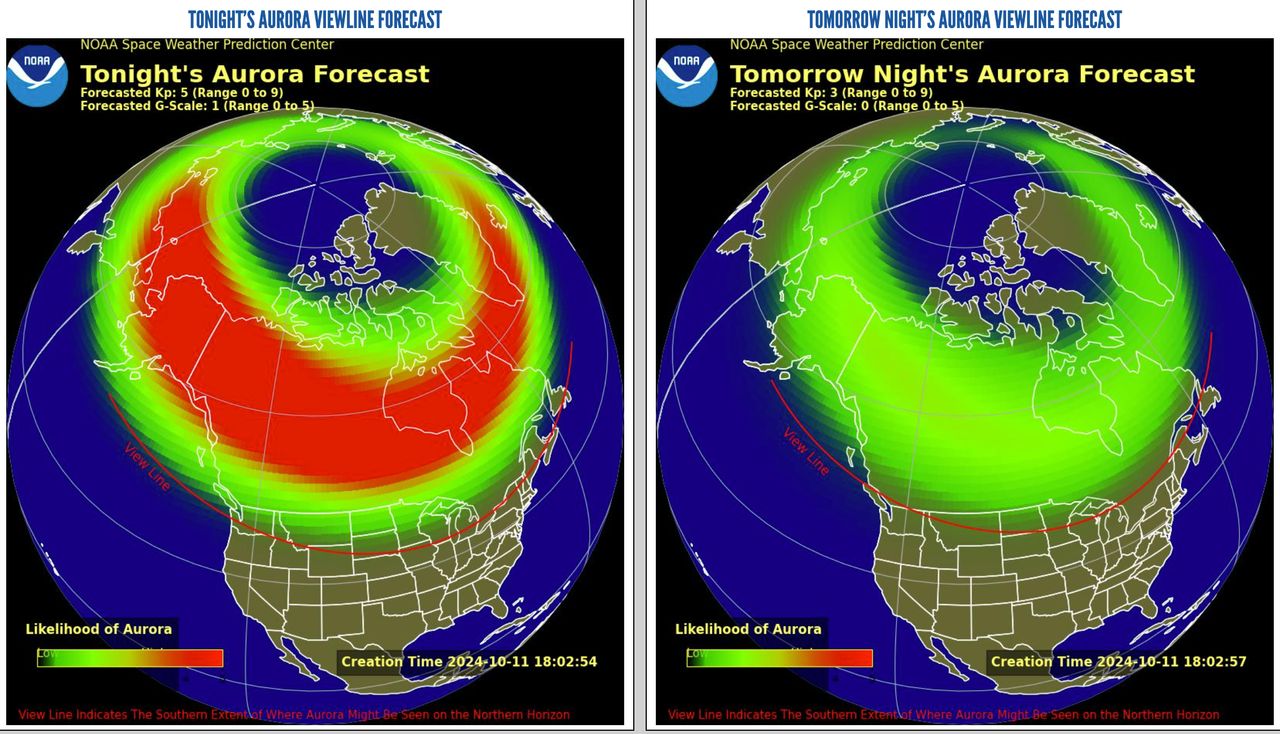

The best opportunity for people farther to the south was Thursday, though people in the northernmost United States (as far south as Iowa) could potentially catch another viewing on Friday, according to a map released by NOAA.

As for when the lights could appear so far south again, Shawn Dahl, the service coordinator for NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center, explained to reporters Wednesday that there could be opportunities well into 2025.

That’s because we are currently in the most active phase of the 11-year solar cycle, called the solar maximum, which is expected to peak possibly in 2025, Dahl said.

“But that doesn’t mean the solar maximum is done. We’ll still be having increased levels of activity or chances for them throughout 2025 and even into 2026,” he said, noting that there’s a lot of energy that has to be released and neutralized.

He added that it would be “highly unusual” for there to be another light show like the one seen in May, which was easily visible in large parts of the southern U.S. That geomagnetic storm was rated a G5. Thursday’s storm was a G4, and Friday’s is forecast to be a G3.

“We’ll still be having increased levels of activity or chances for them throughout 2025 and even into 2026.”

- Shawn Dahl, service coordinator for NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center

“The G5 back in May was the first time we’ve had that since the year 2003. That means we went through the previous solar cycle without ever reaching a G5,” Dahl said.

NOAA has advised viewers to follow its “Aurora Dashboard” website and social media pages for notifications about where the aurora will be seen.

Tips for viewing:

The best time to watch the lights is typically an hour or two before or after midnight. You’ll want to view them from a clear, cloud-free area if possible, NOAA advises.

“There may be aurora in the evening and morning but it is usually not as active and therefore, not as visually appealing,” the agency says.

Most cameras are also better at registering the lights than the human eye.

Miss the lights? Check out some of these photos from Thursday: